NAIROBI, Jan 16 (NNN-AGENCIES) — Kenya’s avocado sector has become so lucrative that organised criminal gangs have begun to target growers.

This is because the fruit from just one tree can pay for the private education of a secondary school student for a whole year – up to $600.

With the demand for the fruit growing in the US and Europe, Kenya overtook South Africa last year to become the continent’s top avocado exporter.

Vigilante groups are now being formed to protect the crop, known as “green gold”.

As night falls on a fairly large farm in the central county of Murang’a, six young men dressed in thick raincoats and armed with torches, machetes and clubs start their shift.

They have been hired to guard the farm and its precious avocados.

It is dangerous work – and people can get hurt and even killed.

“It was either us or them unfortunately and we had to protect ourselves,” one of them tells me, referring to a recent incident in which a suspected avocado thief was killed.

The owner of the farm, which is about half an acre – or half the size of a football pitch, says he has had to take action as he has fallen victim to the thieves.

“You can fence the entire farm but that won’t stop them,” he says, showing me where his barbed wire fence has been cut.

“You spend an entire season taking care of your crops, then in a single night all your fruits are stolen in a matter of hours.”

Another of the vigilantes who is mending the fence agrees: “They’ll still cut it and steal what they want.”

He worries how the community will suffer as most people survive on the trade – many work for those with bigger farms, while most families also have a couple of trees themselves.

“If we sleep, our fathers and mothers won’t have a cent,” he says.

Their watch will end at daybreak.

Avocados tend to be harvested in Kenya between February and October – but the thieves have been targeting the immature fruit.

In an effort to clamp down on the black market, the authorities have imposed a ban on exporting avocados from November until the end of January.

But it is having little effect on the ground – in fact farmers like those in Murang’a county are having to harvest early in order to save their crop from the avocado cartels.

Leaving them on the trees is simply an invitation to the thieves.

In Meru county – about 100km further north – the situation is much worse. We arrive as European buyers are in the area.

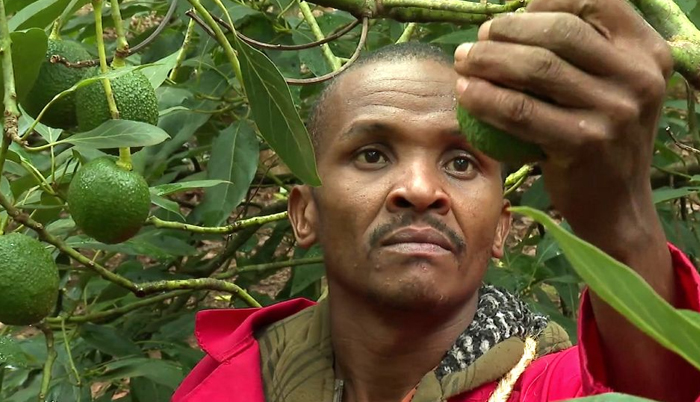

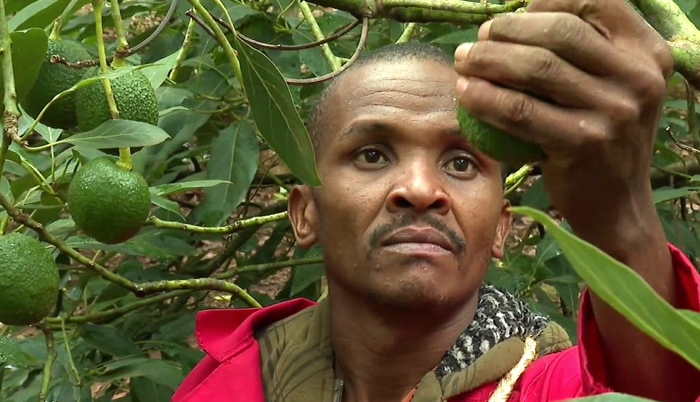

This means some avocado farmers there, like Kinyua Mburugu, are allowed to harvest early.

So in a single day, thousands of hectares of Hass avocados are picked, selling for up to 19 Kenyan shillings each.

The avocados are assessed to ensure quality at the local distribution centre – because if picked too early the fruit will not ripen at all.

For Mburugu, the decision to pick early was taken to keep the thieves at bay.

But in the future he intends to take on the gangs by using a computer purchased through his local avocado co-operative society.

He will connect it to CCTV cameras that he is putting up around his 4.04-hectare farm.

From the comfort of his living room, he intends to keep on eye on his more than 200 mature trees, helped by his tech-savvy son, a film studies graduate.

“My son is thinking of flying drones around so we can have 24/7 surveillance of our farm,” Mburugu says.

As we speak, he receives a phone call. The vigilantes have caught several men who rented a house in the centre of Meru town, part of the cartel stealing fruit.

Later, Julius Kinoti, who heads the neighbourhood watch security team, says they found that the house was full of sacks of stolen avocados.

They alert the police but he warns the authorities need to do more about the problem as people could take matters into their own hands.

“That night we caught those thieves, if I had blown the whistle to alert people, villagers would have come and would have killed them – mob justice – because people are angry.”

Kenya’s avocado trade is still in its infancy, but more and more farmers are deciding to invest in avocados.

Last year, the fruit earned Kenyans farmers $132m from exporting about 10% of the harvested crop, according to the trade ministry.

“If we ensure quality control, we will definitely reach the heights of the big producers like Peru and Brazil,” says Mburugu.

“In the next five years, I don’t think many people here will have tea farms. Avocados are the way to go.”

He uprooted his fields of tea a few years ago – it is not a move he regrets, he just hopes he can keep the avocado cartels at bay. — NNN-AGENCIES